Have you ever been working on a site and think everything is going great until you view your site locally? Maybe you find your images are no longer showing up or an element isn’t floating the way you thought it would. You can see on the browser what the problem is, but maybe it takes you a lot longer to find what the cause of the problem is when you look at your code. There have been times when a simple misplaced semicolon has caused hours of pain. This is why unit testing is so important. You can create tests for your code and if something breaks while you are developing your site the test will alert you that something has broken. This makes it a lot easier to go back to your code and fix the problem. There are many ways to write tests for your code depending on what language you are working with. I want to focus on JavaScript in this blog post so we are going to look at QUnit for creating tests.

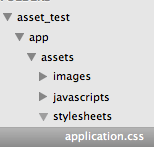

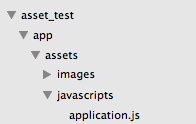

A good place to start is to look at the documentation for QUnit. Here you will be able to find examples as well as download the documents you need to create your own test. You will have to download the first two files and place them into your sites directory.

We are also going to be referring back to the API documentation a lot, because it contains a full list of all the assertions we can use to create tests. What if you wanted to make sure that two objects were equal? You could use the “propEqual” assertion. Below is an example of using “propEqual”.

First we need to set up our html file.

<!DOCTYPE html>

<html>

<head>

<meta charset="utf-8">

<title>propEqual Example</title>

<link rel="stylesheet" href="qunit-1.15.0.css">

</head>

<body>

<div id="qunit"></div>

<div id="qunit-fixture"></div>

<script src="qunit-1.15.0.js"></script>

<script src="propEqualTest.js"></script>

</body>

</html>

Above in the <head> tag of the document we have a link to the css file that we downloaded from the QUnit site. At the bottom of the <body> tag we are linking to two JavaScript files. The first file is also downloaded from the QUnit site and the second file is one that we are going to create all of our tests in. Lets add some tests in the “propEqualTest.js” file.

test('testing propEqual', function() {

propEqual( {animal: 'tiger'}, {animal: 'tiger'}, 'same objects, test passes');

propEqual( {fish: 'goldfish'}, {fish: 'dog'}, 'not the same, test fails');

})

Above we have a function called “test” which gets called from the “qunit-1.15.0.js” file. This function has two arguments. The first argument is a string which is just labeling the test we are creating. The second argument is a callback function which is where we are using “propEqual” to create the test. The “propEqual” assertion is defined in the API documentation. What we are doing above is comparing the first two arguments of the “propEqual” assertion with each other. If the objects are the same the test will pass, because it evaluates to true and if they don’t match they will evaluate to false. Now lets look at how the html document looks when we open it in a browser.

The first test passed and we see that our message “same objects, test passes” in green. The second test failed so we see our message “not the same, test fails” appear in red. We also see what the differences were between the two objects which caused our test to fail. You can see how helpful writing tests becomes when working on developing a site.

Below is a list of resources for QUnit: